The vast and varied landscape of fine art is worth exploring far beyond thought-provoking street artists. Great works of art have indeed been reliable and satisfying investments. There have been notable high-profile sales in recent years, including works by Picasso, Klimt, Warhol, Cézanne, and van Gogh: a testament to an exciting and booming market. For instance, let us trace the journey of Picasso's “Les Femmes d'Alger, Version O” over the years. It was originally sold for $26,632 in 1966, then auctioned for $31.9 million in 1997, finally changing hands again in 2015 for $179.3 million. It held the title of the most expensive painting auctioned for the next 2 years, until the sale of a da Vinci painting in 2017 ($559.7 million; it holds the record for the most expensive painting sold to this day, by a large margin). I wonder if Picasso, a notorious egomaniac, would be honoured or insulted at being knocked off the top by Master Leonardo himself. For those following the figures above, I crunched the numbers for you—adjusted for inflation, “Les Femmes d'Alger, Version O” increased in value by 1000% between 1966 and 2015.

I look at these accounts through the lens of art history and acknowledge that these works are priceless because of their cultural heritage and artistic significance. But some of them are literally priceless because they have never been sold, and thus do not have a price to speak of. Setting aside famous works that are owned by governments or other institutions, often donated, behind every canvas there is someone who treasures it beyond its ROI or its blue-chip status. Often, these works are generously shared with the public in museums and private galleries across the world, something visitors rarely think about.

Unquestionably, high-profile fine art and remarkable historical items have established themselves as prized assets, solid investments destined to increase in value impressively over decades, centuries, and even millennia, and this is not an exaggeration. A unique collectable (if it can even be called that), a historical artefact dating back to the late ninth or early 10th century, was sold in 2023 at a Sotheby's auction in New York—The Codex Sassoon, one of the world's oldest manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible—for $38.1 million. It had been previously sold at an auction in 1989, for $3.19 million, about $8 million in today’s dollars. It will be donated to a museum and made available for the public to enjoy.

On behalf of enthusiasts and art lovers everywhere, I declare that the acquisition of treasure assets with the genuine intent to admire, share, or otherwise consume is more meaningful than acquisition intending to yield a return.

In the case of less prominent collectables, some novelty or niche items can also be perceived as part of a diversification strategy, but multiple factors can eat into the potential returns. For example, the costs of storage, upkeep, and insurance, coupled with high transaction fees for specialized sales—sometimes averaging up to 30% for certain categories of assets—will have a significant impact. Besides, there is no guarantee that the anticipated market price will match the eventual selling price. At auctions, it is not uncommon that such assets sell at markedly lower prices. One can analyse all the reports and rely on expert opinions when purchasing wines, cars, gemstones, or any other passion asset. But the reality remains uncertain; the value of all of them is ultimately subjective, and somehow, this seems to be a controversial statement.

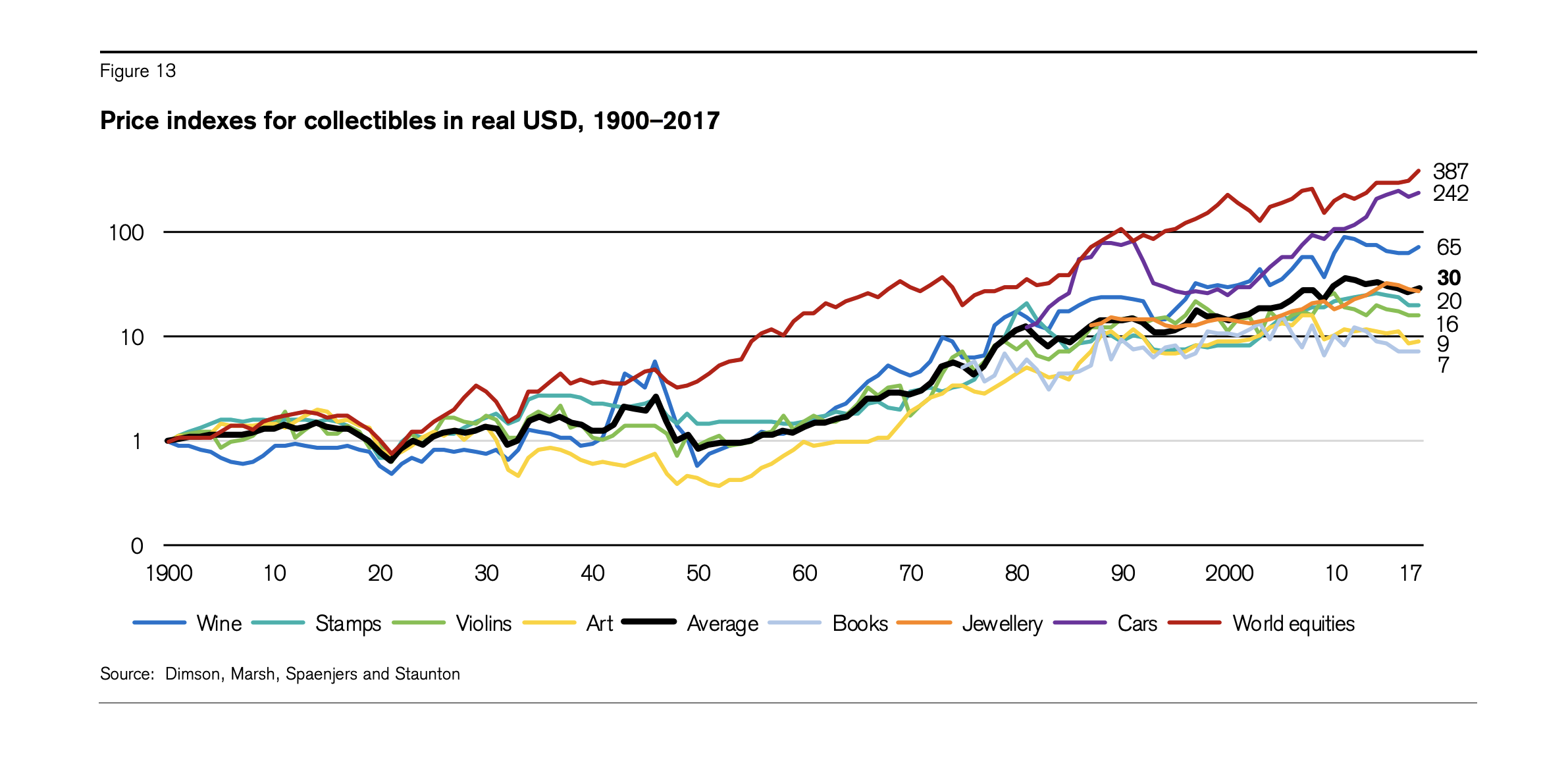

Back in 2017, researchers from the London Business School assembled a detailed report on the investment performance of non-financial assets over the past 118 years. It was published in a Credit Suisse Yearbook that same year. This is an important piece of the asset puzzle, as, according to Knight Frank, about 6% of global assets of UHNWIs are allocated to collectables such as art, cars, wine, etc.

Based on the data, classic cars seem to have performed best, followed by jewellery, books, and fine art. However, according to the report, all collectables have underperformed compared to the world equity index over the last 100 years. Keep in mind that historical performance is a poor indicator of future performance.

Some treasure assets are pro-cyclical, their value going up and down, mirroring the general trends of the economy. Others are counter-cyclical. In general, counter-cyclical assets, such as classic cars, seem to offer more diversification benefits.

With the advancement of technology, climate change policies, and the general shift towards electrification, the classic car market is increasingly driven by nostalgia. Accelerated by the pandemic, the bulk of sales is moving towards online auctions. California-based Bring a Trailer has had a huge impact on the market, and the development and expansion of similar platforms will definitely affect supply, demand, and returns. The classic car market is growing, and new buyers are, to an even larger extent, regarding their automobiles as stores of value and do not drive them. Historic vehicles are, on average, driven 15 times a year, spanning about 1,400 km.

Another challenge is that rarely are two collectables exactly the same. I have sifted through a plethora of colourful charts from reputable sources (see footnote). The fact that some of them have to go into considerable detail and differentiate between, say, the performance of Latin American art compared to traditional Chinese art, or Chanel bags compared to Birkin bags in a given year, due to substantial differences in returns, only supports my point. If you are into Indonesian sculpture and the market for it is dormant, how can returns be accurately assessed? Even if we try to compare artworks by the same artist, they are far from consistent and vary wildly based on seemingly arbitrary perceptions of societal and cultural value. What if you have terrible taste? Of course, YOU don't, but others might.

It seems curious, but scarcity does not always guarantee an increase in value. The generation gap is a peculiarity— younger generations may not be interested in the collectables cherished by previous generations. Stamps and antique furniture, even lesser known Old Masters paintings, among others, have not done well. I bet Kanye's worn sneakers, NFTs, and “rare” Pokémon cards will face the same fate, but, for now, you'll have to take my word for it. Sometimes, interest in something quietly wanes, and you are left holding the bag, so to speak. But if it's a Chanel bag, and you love it, should you even care?

Every asset comes with an asterisk (pun intended). For watches, service and upkeep that improve their wearability will devalue them over time. Counterfeiting is a known issue that especially plagues the art and wine markets, but no collectable is immune to forgeries. There are numerous stories of recorded sales surpassing the documented amount of genuine goods produced. Gems and jewellery mark milestones, compactly store value, and can have special social, historical, and artistic significance. However, the push for sustainability, traceability, and transparency of supply chains puts pressure on both big names and small producers and mining companies. Wines are sensitive to storage and transportation, while insurance costs can reach $2.50 per bottle per year. Some wines age worse than others, especially those with lower sulphur content, and some are prone to spoiling through turbidity.

I find all of this symbolic and in favour of my point. Enjoying and consuming come in opposition to pure collecting with the goal of storing value. Not everything has to be an investment, and your prized collection is unlikely to insulate you from inflation. Passion assets are a form of self-expression. Un-Marie-Kondo and acquire what brings you joy.